Big Bend National Park is home to more than 1,200 species of plants. Of those, there are 60 different species of cacti. In fact, there are more types of cacti in this park than in any other National Park or in the entire state of Arizona.

Let that sink in, ya plant geeks (I mean, botanists!).

Between the Chihuahuan Desert, the Rio Grande, and the mountain slopes, this park offers incredible diversity in both landscape and life. You will find species ranging from orchids to willows, and from desert succulents to pine trees.

Table of Contents

Read on for breakdown of the four major plant communities you’ll encounter.

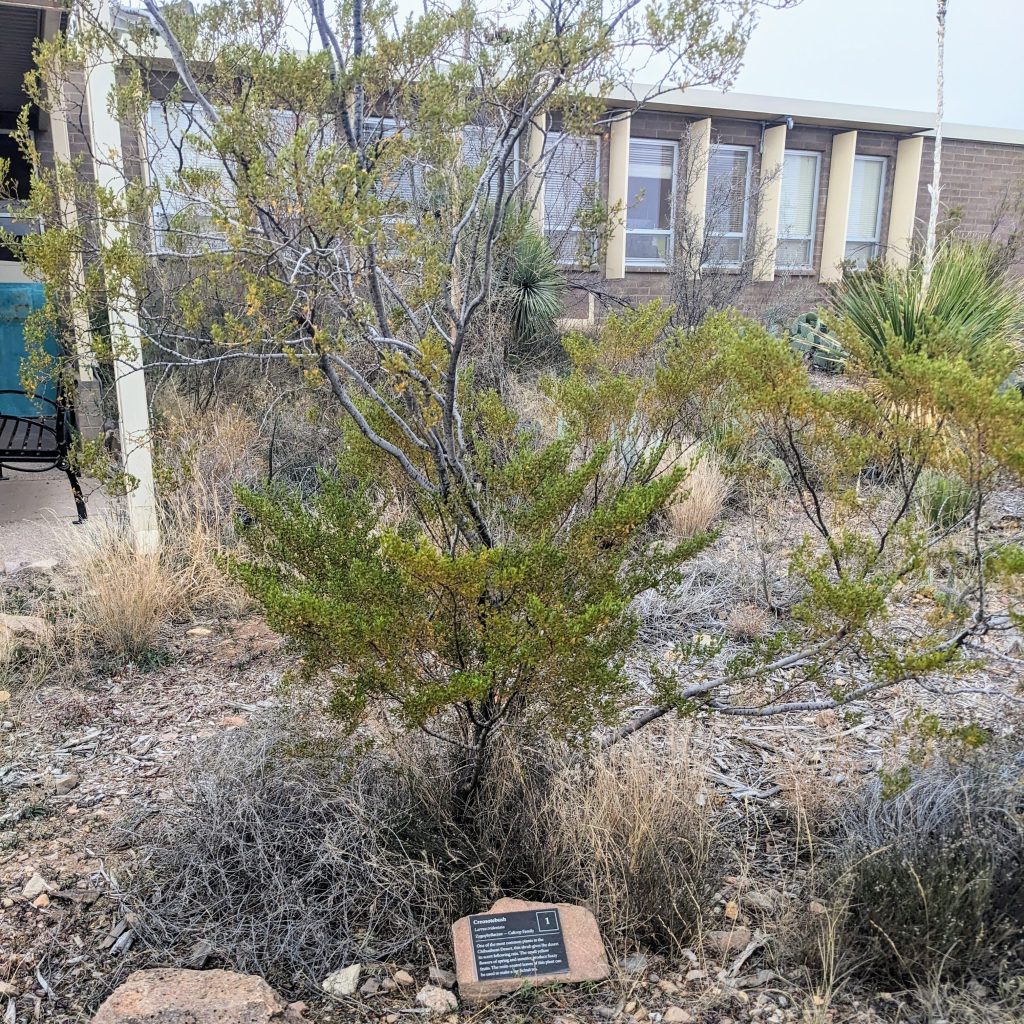

Desert Scrub (Most Common)

This is the most common type of vegetation in the park and it occupies the lower elevations. Examples of desert scrub found in Big Bend are Creosote bush, a classic desert plant, as well as Yucca, Ocotillo, Lechuguilla and Cacti.

Many of these plants are either thorny or sharp in one way or another. Good sturdy shoes and pants are a must for traipsing around Big Bend!

So many sharp things waiting to stab you…

The Yucca Plant (Nature’s Laxative?)

Because one just isn’t enough, there are four different kinds of Yucca within BBNP.

Yuccas flower each year if there is enough rain. The flower buds, petals, young stalks, fruits, and seeds are all edible. The leaves were historically used to make cloth, rope, sandals and baskets.

And should you happen to need a laxative (heavy camp dinner, eh?), my research says the Yucca roots can provide!

Agave Lechuguilla

Also of particular interest is Lechuguilla Agave (I’ve heard it both ways), whose name means “small lettuce”. These plants are better known to some as “shin daggers”, though they’re hardly the only offenders to be found in this desert. This gem is only found within the Chihuahuan Desert – it grows nowhere else.

Lechuguilla have thick leaves and sharp spines. This plant grows for 12-15 years, storing up enough food to produce a large flower stalk. Once it has enough food, the flower stalk shoots up with rapid speed, up to 15 feet tall.

After producing flowers and seeds, it dies.

Sad.

Desert Grassland (Threatened)

You’ll find desert grasslands a bit higher up. They occupy the lower slopes of the Chisos Mountains (as well as other mountains) and tall hills between 3,500-5,000 feet of elevation. Deeper soil and more generous rainfall support Bluestems, Needlegrass, Blue Grama and Tobosa Grass.

Unfortunately, early settlers were not good stewards of the land. The early 1900’s and reckless disregard for natural ecosystems, name a better pair! Overgrazing led to soil erosion, and allowed desert scrub to come creeping into this habitat. Big Bend’s desert grasslands look much different today than they did just 150 years ago.

The Sotol Plant (and a Booze Review)

Chinograss and sotol are other classic examples of desert grassland flora that you’ll see everywhere. Sotol is especially hard to miss, and notable for more than its massive stalks.

For starters, it was long important for basket weaving and related trades in the region. When the plant is young, the flower stalks and seeds are edible, along with the plant’s heart.

When the sap ferments it produces an alcoholic beverage, also called Sotol. They say it’s similar to Tequila, and I guess that’s true if you squint. I gave it a try in Terlingua – you can get it at most bars in that area. Sad to say, either it’s shit or the bartender was.

Sorry Sotol lovers!

Pinyon-Juniper-Oak Woodland (Higher Elevations)

Somewhere around 4000 feet of elevation, you begin to enter a whole new world. At the higher and cooler elevations in the Chisos, Piñon, Oak, Juniper, Bigtooth Maple and Madrone grace the land. There on the forested slopes it feels like the desert is far, far away.

This is the beauty and allure of Big Bend. As you explore, it feels like you are moving between different parks with so many different ecosystems. Sometimes all within the space of a single fucking hike!

Even within the woodlands, there’s considerable diversity. In fact, some of the trees here are quite special. Scientists recently discovered a species of Oak tree once believed to be extinct. And that’s just one of nine species of Oak growing in the park’s forests.

Texas Madrone

Texas Madrone trees like to hide in moist canyons – and there are plenty of those. The Madrone is actually a rain forest relict. This means that it’s a remnant from a long ago diverse and widespread population of trees.

It produces fragrant pink or white flowers in spring and bright red fruit in fall, which Native Americans of the region harvested. The tree itself has a gnarled trunk with reddish bark and grows to around 30 feet tall.

Weeping Junipers

Another special tree is one native not only to Texas, but to the Chisos Mountains themselves. The Weeping Juniper (pictured below) prefers high elevations and igneous soils, and has a distinctive appearance.

It reminds me – who, I must admit is not even close to a botanist – of a Weeping Willow. Hence the name, I assume.

Anyway, the Weeping Juniper lives a long life and is quite drought resistant. Though with its droopy branches, it looks as if it is in constant in need of a cold drink to perk it up – maybe a Shiner?

Ponderosa Pine-Douglas Fir-Arizona Cypress Forest

Last but certainly not least, this is my favorite flora biome in the park. This ecosystem is often referred to as a “sky island”, a habitat in high elevations surrounded by a “sea” of desert.

Sky Islands (Skylands?)

In these “sky islands”, the high altitude provides lower temperature and higher precipitation. Here you will see plants and animals found nowhere else in Texas.

Many of these trees are more typically found in northern regions (aka, not Texas). Like the Madrone, they are leftovers from a very different time in Big Bend.

Listening to the wind whisper through the needles of the pines blows peace and strength my way. Being surrounded by the greenery these forests bring is refreshing in a way that the desert down below is not.

Ponderosa Pines are common in many other parts of the country. But in God’s country – Texas, I mean – you’ll find them only in the Davis Mountains, Guadalupe Mountains and Big Bend’s Chisos Mountains. These ranges all provide the previously mentioned high elevation “islands” they need to survive here.

Plants Playing Hard to get

What’s really neat about these forests is that you have to want to see them in order to get to them. And I mean you really have to want it. There are no roads to drive on up to that sacred island in the sky. No, you have to haul your ass up there on foot.

I’m talking from down low in the Chisos Basin up thousands of feet of elevation pain (gain) to reach these fucking slopes.

If that sounds like your type of fun, read on.

How to see all four Big Bend Biomes in one Hike

So your curiosity is piqued and you want to get out there and see all this gorgeous nature for yourself?

Excellent. I can make it easy for you.

In fact, you even get a choice between two different hikes that will span the full gamut of Big Bend flora.

First up is the most adventurous and, in my opinion, breathtaking option: Hike the Rim in Big Bend National Park.

This hike includes the best views in the park, but it’s not for the faint of heart. I definitely recommend reading about my experiences before booking your campsite.

If that’s a bit too intense for you, don’t despair. Your backup option has some spectacular views too, although it’s not exactly easy.

I’m talking about hiking to Emory Peak, of course.

It may be easier and shorter than doing The Rim, but there’s still some serious elevation gain involved. Remember what I said about needing to want to see the sky island biomes?

Too Long: Didn’t Read;

Honestly, this article is mostly pictures anyway.

- Desert Scrub is thorny, sharp, and everywhere at lower elevations.

- Desert Grasslands are less common than they once were. Keep an eye out for Sotol plants throughout the park, but be prepared when trying the drink made from them.

- Around 4000 feet up, Pinyon-Juniper-Oak Woodlands begin to take over and it feels like a completely different park.

- Way up high, you’ll see a different type of forest, filled with Ponderosa Pine, Douglas Fir, and Arizona Cypress. These trees are rare in Texas, found only in “Sky Islands” with cool temps and more rain.

- See them all by hiking The Rim! If that sounds crazy, you can get a similar experience hiking Emory Peak.

Thanks for stopping by! I hope you learned something, or at least were mildly entertained. Now get off your damn screen! Go forth and enjoy the splendors of nature this park has to offer.

Which biomes are your favorite? Feel free to share your thoughts (and photos) here!